Zoltán Bay and the Moon radar experiment

"I saw the Moon walking behind the tower and asked the adults: If I climbed the tower, would I be able to touch the Moon?"

These words came from the mouth of Zoltán Bay as a child, when, at only a few years old, he looked up at our celestial companion with awe. Perhaps it was this childlike curiosity that led him, four decades later, in 1946, to successfully reach the surface of the Moon with his radar experiment, albeit only with radio signals.

Zoltán Bay is one of a number of Hungarian scientists whose work has been undeservedly forgotten in our country. Like many of his contemporaries, he spent half his life working and living overseas, but he made his discoveries and conducted his experiments of scientific historical significance at home. His life could easily have turned out completely differently, as Bay, faced with choosing a career, could not decide whether to pursue a profession in the arts, social sciences, or natural sciences. Luckily, his role model, Loránd Eötvös, steered his interest toward physics, otherwise we might now remember him as a mediocre painter or a forgotten sociologist. Instead, he is remembered today as the father of radio astronomy. However, it was a long road to earning this prestigious title.

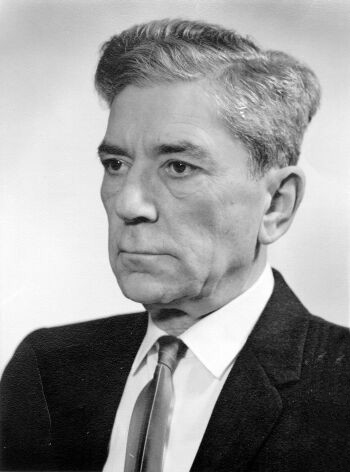

Zoltán Bay

After graduating, he got a research job in Berlin, where he did research on moon radar. After returning from Germany, he continued his work at the Budapest University of Technology and the Tungsram Laboratory. But it's not just radar experiments that are linked to his name, as a significant achievement in physics, as he also had several patents: the development of high-voltage gas tubes, fluorescent tubes, and electron tubes, a patent on electroluminescence, the development of radio receiver circuits, and decimeter radio wave technology.

Like many other discoveries of great significance, the success of the moon radar experiments was due to the war and the related developments in military technology. Hungary's entry into World War II meant that the country's territory would be subject to bombing raids. In every country at war, both on the enemy and allied sides, scientists were thinking about how to detect enemy aircraft entering the atmosphere as early as possible. However, each country kept its research in this area strictly secret, so the Hungarian Armed Forces had to develop its own technology. In 1942, the so-called Bay Group was established, whose task was to conduct microwave experiments, i.e., to develop a radar and introduce microwave communications. The team included several renowned researchers, such as Károly Simonyi.

The Bay Group completed its assigned tasks within two years. They solved the problem of microwave communication, and by 1944, a radar system had been put into operation that could detect enemy aircraft from a distance of more than 60 kilometers, allowing bombers heading for Székesfehérvár to be detected even over Budapest. Bay then stood before his colleagues and said, "We are going to locate the Moon!" The new challenge not only excited the researchers, but the army also approved the developments. After another two years, this brilliant experiment was successfully completed, and it was only a few weeks ago that we began to refer to the group's researchers as the first to have accomplished this extraordinary feat. Although the team owed its existence to the war, it was precisely the vicissitudes of war that constantly hampered their work. Due to the current combat conditions, the group's premises and experimental equipment had to be moved more than once.

For a while, the experiments were conducted in Nógrádverőce, but without any significant results. This is not surprising, as the conditions were unsatisfactory, for example, the power supply was inadequate.

Due to the proximity of the front, they were soon relocated to the United Light Bulb factory in Újpest.

The vicissitudes did not end there, however, as the group lost its legitimacy with the Arrow Cross takeover, several of the researchers were conscripted, and those of Jewish origin were in mortal danger—Bay risked his life to protect many of them. The situation did not improve with the end of the war, as Soviet troops occupied and looted the factory, taking everything, including the equipment developed for the radar experiments. Despite all this, Bay was determined to continue his work, and on February 6, 1946, their efforts were crowned with success. Only then did they learn that a few weeks earlier, American researchers had already succeeded in detecting radar signals from the Moon, but the technology Bay and his colleagues were working with was unique to them. Let's see how our compatriots managed to detect radar signals.

The Moon radar

Since radio astronomy as a concept did not yet exist at that time, the group's researchers had to lay the groundwork for it. There were even more problems to be solved that would have a decisive impact on the success of the experiment. The most important questions to be answered were: can microwave signals escape into space at all, to what extent does the Moon reflect the signals, how do these signals propagate in space, and can they be detected on Earth? The Bayes answered each of these questions in theory, but the question was whether they could be proven in practice. They believed that signals with a wavelength of 1 meter could pass through the Earth's ionosphere unimpeded and without loss. Since the Earth's surface has a reflectivity of about 10%, they assumed the same value for the Moon, and according to their theory, the reflected signal would be evenly scattered in space. However, detecting the returning signals posed a more serious problem. Let us not forget that the Moon is extremely far away on a terrestrial scale, orbiting more than 380,000 kilometers from us. It is not easy to bridge this distance, as the strength of the signals decreases proportionally with distance. Based on this, the signal-to-noise ratio during detection was estimated to be 1/10, which was too low. Then Bay came up with a brilliant idea, which was new even to American researchers working with much more modern equipment, namely that the received signals should be summed up by continuously repeating the transmission of the signals. Microwave signals take 2.5 seconds to travel the distance between the Earth and the Moon. Based on this, the researchers calculated a 50-minute operating time, during which the returning signals must be continuously transmitted and stored. They obtained this value by transmitting a signal every 3 seconds, which means that 50 minutes are needed to store 1,000 usable signals.

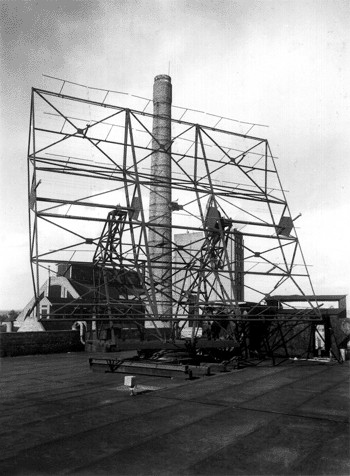

However, this solution was a serious challenge at the time, as there were no devices (e.g., computers) available that could do this without any difficulty. The development of the appropriate device is attributed to Andor Budincsevics and his colleague, Emil Várbíró, who designed a so-called hydrogen coulometer to store the signals. This succeeded in increasing the signal-to-noise ratio thirtyfold. Initially, they used a three-meter parabolic antenna and tried signals with a wavelength of half a meter, without success. The vicissitudes of war and the confiscation of the antenna by the Soviets prevented further experiments. In 1945, when the group's work was successfully restarted, they tried using a reconnaissance radar obtained from the army. This also posed a problem: its wavelength was 2.5 meters, so the antenna surface had to be increased. In addition to the specific lunar radar experiments, blind tests also had to be carried out to provide a basis for distinguishing between plain noise and useful information. Finally, on February 6, 1946, the signal level in the coulometer, which summarized the signals, exceeded the value measured by the device set up solely to detect noise by 4%. Bay and his colleagues considered this to be such a high value that they declared the experiment a success. The Moon's signal-reflecting capacity was estimated on the spot, based on the results obtained. Bay's unique invention, the signal summation method, is still used in radio astronomy today.

His plans included the development of a giant radio telescope, which would have consisted of nothing more than a large cauldron dug into the ground and covered with metal. However, it was never realized.

Despite persuasion and potential supporters, after seeing the technology used in America, he decided he could not compete with them. However, his idea did not fade away, as the Arecibo (Puerto Rico) radio telescope, the largest of its kind, was built on this principle.

The Arecibo Observatory

Despite his success and international recognition, he left Hungary due to changes in the political situation and continued his work in America. However, he never forgot where he came from, so let us conclude with a quote from him:

"I often visit Hungary. I have never denied that I am Hungarian. I will remain Hungarian as long as I walk the Earth."